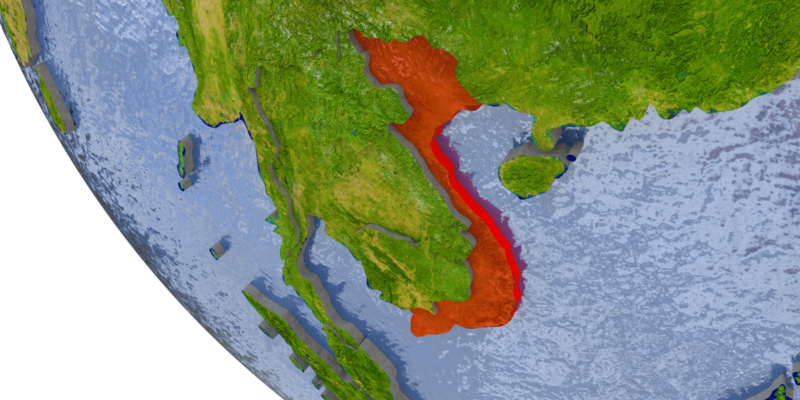

Vietnam’s “Liberation”

Historical Context

The Vietnam War, a prolonged and devastating conflict, began as a struggle between North and South Vietnam but quickly escalated into a major conflict involving global powers. The North, led by the communist government, sought to reunify the country under its rule, while the South, supported by the United States and other Western allies, fought to maintain its separate, non-communist government. Over the years, the war caused immense suffering, with millions of lives lost and countless others affected by the destruction and trauma. The Vietnamese people endured tremendous sacrifices, facing not only the horrors of war but also the widespread disruption of their daily lives.

The involvement of foreign powers, particularly the United States and the Soviet Union, turned Vietnam into a battleground for Cold War tensions. The heavy military intervention and the introduction of modern warfare by these global powers intensified the conflict, leading to significant casualties and widespread devastation. However, despite these overwhelming challenges, the resilience and determination of the Vietnamese people never wavered. Their relentless pursuit of independence ultimately led to the historic event known as “Liberation,” culminating on 30 April 1975 with the fall of Saigon, the end of the war, and the reunification of Vietnam.

The Progress of the “Liberation” Event

The Spring Offensive of 1975, known as the Ho Chi Minh Campaign, was a decisive and carefully coordinated military campaign that led to the liberation of South Vietnam and the reunification of the country. Beginning in March 1975, the North Vietnamese forces launched a series of rapid and strategic attacks, capitalising on their momentum after years of gruelling warfare. This offensive was marked by several key battles, each contributing to the swift collapse of the Saigon government.

One of the most significant engagements was the Battle of Ban Me Thuot in March 1975, where the North Vietnamese forces captured the strategic Central Highlands, effectively cutting South Vietnam in half and triggering a domino effect of retreats and surrenders by the South Vietnamese army. Following this victory, the North’s forces moved quickly, capturing key cities such as Hue and Da Nang, which further destabilised the South’s defences.

As the campaign progressed, the North Vietnamese army, bolstered by the unwavering support and unity of the Vietnamese people, pushed relentlessly towards Saigon. The final assault on Saigon, commencing in late April 1975, saw the swift and decisive advance of the North Vietnamese troops, who encountered minimal resistance as the morale and organisation of the South Vietnamese forces crumbled. On 30 April 1975, a North Vietnamese tank famously crashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace in Saigon, symbolising the end of the war and the fall of the Saigon government.

This momentous victory was not just a military triumph but also a testament to the indomitable spirit and unity of the Vietnamese people, who had endured immense suffering and loss over the years. Their determination, coupled with strategic military leadership, led to the successful conclusion of the war, bringing about the long-sought-after reunification of Vietnam.

Significance of “Liberation”

The “Liberation” of 30 April 1975 marked a monumental turning point in Vietnam’s history, bringing an end to decades of war and achieving the long-sought goal of national reunification. With the fall of Saigon, the country was finally united under one government, ending the division that had torn Vietnam apart for over 20 years. This event not only signalled the conclusion of a brutal and devastating conflict but also laid the foundation for a new era of peace, independence, and national reconstruction.

The end of the war and the reunification of Vietnam opened the door to a future of freedom and development. After years of resistance and sacrifice, the Vietnamese people could finally begin the process of rebuilding their country, focusing on economic growth, social stability, and the preservation of their cultural heritage. The “Liberation” marked the start of a period of recovery and rejuvenation, as Vietnam embarked on the path towards becoming a unified and prosperous nation.

Psychologically and spiritually, the victory of 1975 had a profound impact on the Vietnamese people. It restored a sense of national pride and dignity, reaffirming the strength and resilience of a nation that had endured unimaginable hardship. The successful reunification also strengthened the collective identity of the Vietnamese people, fostering a sense of solidarity and shared purpose that continues to shape the country’s social fabric.

On the international stage, the “Liberation” of Vietnam had significant repercussions. It marked the end of foreign intervention in the country’s affairs and solidified Vietnam’s position as an independent and sovereign state. The reunification also influenced Vietnam’s diplomatic relations, as the country sought to establish itself within the global community, navigating the complexities of Cold War geopolitics and forging new alliances in the post-war world.

In essence, the “Liberation” of 1975 was a watershed moment in Vietnam’s history, bringing peace, unity, and a renewed sense of national identity. It paved the way for the country’s transformation from a war-torn land to a nation focused on growth, development, and international cooperation.

Vietnam After “Liberation”

Following the “Liberation” of 1975, Vietnam faced immense challenges in the process of rebuilding and developing the country. The war had left the nation devastated, with infrastructure in ruins, economies disrupted, and millions of lives affected by the conflict. The immediate years after reunification were marked by efforts to restore the country’s basic functions, including rebuilding cities, restoring transportation networks, and revitalising agricultural production. The government also faced the complex task of integrating the North and South, which had been divided for decades, both socially and economically. These efforts were further complicated by international isolation, as Vietnam grappled with economic embargoes and a lack of foreign aid.

Despite these daunting obstacles, Vietnam made significant strides in its reconstruction and development. The country embarked on a path of economic reform, most notably with the introduction of the Đổi Mới (Renovation) policy in 1986, which transitioned the economy from a centrally planned system to a socialist-oriented market economy. This shift led to remarkable economic growth, improving living standards and reducing poverty across the nation. In addition to economic achievements, Vietnam also made progress in education, healthcare, and cultural preservation. The literacy rate increased, access to healthcare expanded, and cultural initiatives were launched to preserve and promote Vietnam’s rich heritage.

The “Liberation” of 1975 played a crucial role in shaping modern Vietnam. It not only unified the country but also set the stage for its transformation into a dynamic and rapidly developing nation. The victory instilled a sense of resilience and self-reliance that has continued to drive Vietnam’s progress. The post-liberation era saw Vietnam emerge as a country committed to peace, stability, and international cooperation, steadily integrating itself into the global economy and gaining recognition as a key player in Southeast Asia.

In summary, while Vietnam faced significant hardships in the aftermath of “Liberation,” the determination to rebuild and develop the nation led to substantial achievements in various fields. The unification of Vietnam under a single government has been instrumental in the country’s journey toward modernisation, laying the foundation for the economic growth and social development that define Vietnam today.

“Liberation” in the Memory of the Vietnamese People

The “Liberation” of 1975 holds a profound place in the collective memory of the Vietnamese people, evoking a wide range of emotions and reflections. For those who lived through the war, the day of liberation is often remembered with a mix of relief, joy, and sorrow. Many recall the overwhelming sense of pride and unity that swept the nation as the country was finally reunited after years of division and conflict. The stories of bravery, resilience, and sacrifice—both on the battlefield and at home—are passed down through generations, serving as a testament to the strength of the Vietnamese spirit. These personal accounts, whether of soldiers who fought on the front lines or civilians who endured the hardships of war, are deeply intertwined with the narrative of national liberation.

There is a strong sense of pride and gratitude among the Vietnamese people towards those who made the ultimate sacrifice for the country’s independence and freedom. Monuments, memorials, and annual commemorations are dedicated to honouring the fallen heroes who gave their lives for the cause of national unity. This collective remembrance is not just about honouring the past but also about reinforcing the values of patriotism, perseverance, and resilience that defined the struggle for liberation.

Passing on the lessons and values of “Liberation” to younger generations is seen as a vital responsibility. Schools, museums, and cultural institutions play an important role in educating the youth about the significance of this historic event. Through history lessons, storytelling, and public commemorations, the legacy of “Liberation” is kept alive, ensuring that future generations understand the sacrifices that were made and the importance of safeguarding the hard-won peace and independence. These efforts help instil a sense of national pride and continuity, reminding young people of their heritage and the enduring values that continue to shape Vietnam’s identity.

In conclusion, the “Liberation” of 1975 remains a deeply significant and emotional event in the hearts of the Vietnamese people. It is a time of reflection, honouring the sacrifices of those who fought for freedom, and a commitment to passing on the lessons of resilience and unity to future generations. Through these shared memories and values, the spirit of “Liberation” continues to inspire and guide the nation.

Conclusion

The “Liberation” of 1975 stands as a defining moment in Vietnam’s history, marking the end of a long and painful conflict and the beginning of a new era of unity and independence. This event not only brought about the reunification of a divided nation but also laid the foundation for the rapid development and modernization that Vietnam has experienced in the decades since. The significance of “Liberation” extends beyond the immediate victory; it serves as a powerful reminder of the resilience, determination, and sacrifice that enabled the Vietnamese people to overcome immense challenges.

From the struggles of the past, Vietnam has drawn invaluable lessons—lessons of perseverance, unity, and the importance of national solidarity. As the country continues to evolve, these lessons remain as relevant as ever, guiding its progress and shaping its future. Looking ahead, it is essential to remember the spirit of “Liberation” as a source of strength and inspiration, fostering a sense of national pride and a commitment to building a better, more prosperous future for all.

In this spirit, we must continue to embrace the values of unity, reconciliation, and cooperation, working together to overcome challenges and achieve common goals. By doing so, we can honour the legacy of those who fought for our freedom and ensure that Vietnam’s future is one of peace, progress, and shared prosperity.