Buddhism

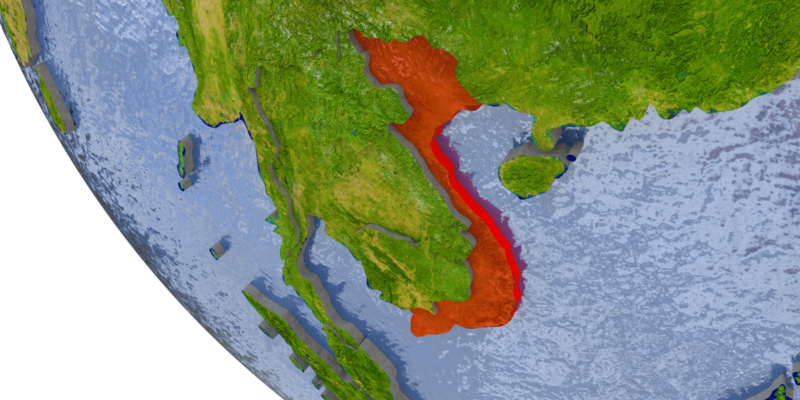

Buddhism’s journey through Vietnam is a profound example of religious evolution and cultural integration, reflecting centuries of socio-political shifts and spiritual practices. From its roots in India, Buddhism traveled across Asia, morphing into distinct forms that mirrored the local cultures of the regions it penetrated.

Theravada and Mahayana: The Two Paths

The divergence between Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism represents more than geographical separation; it signifies deep philosophical differences. Theravada Buddhism, known for its austerity and close adherence to the Buddha’s original teachings, focuses on personal enlightenment and the attainment of Nirvana. This form of Buddhism appeals to those who value introspection and rigorous meditation, embodying a minimalist approach to religious life that shuns the elaborate rituals associated with later Buddhist traditions.

In contrast, Mahayana Buddhism presents a more accessible approach, incorporating spiritual beings or Bodhisattvas who delay their own salvation to assist others in achieving enlightenment. This branch is characterized by its inclusivity, offering multiple paths to enlightenment, which can involve devotional practices, rituals, and a pantheon of celestial Bodhisattvas. The Mahayana belief in Sukhavati, or the Pure Land, a kind of Buddhist heaven, shows its flexibility in adapting to local cultural elements, including those from Hinduism and Taoism.

Buddhism’s Vietnamese Adaptation

When Buddhism reached Vietnam, it adapted to local conditions and split into various sects, each reflecting different aspects of Vietnamese culture and regional influences. In Northern Vietnam, Mahayana Buddhism took a distinctive form with the establishment of the Thien (Zen) sect, centered around the serene Yen Tu mountain. This sect emphasizes meditation and direct discovery of one’s nature, making the sacred mountain a pilgrimage site with its pagodas and monastic institutions nestled in tranquil forest settings. The development of infrastructure like cable cars has made this spiritual heritage more accessible to both pilgrims and tourists.

The Dao Trang (Pure Land) sect, predominantly in Southern Vietnam, focuses on veneration of A Di Da, the Buddha of the past, reflecting the more devotional aspects of Mahayana. This sect illustrates the typical Mahayana trait of seeking aid from celestial Buddhas to achieve enlightenment, appealing particularly to lay Buddhists for its accessible practices and the hope of rebirth in a pure land.

Minority and Militant Sects

Theravada Buddhism still persists among the Khmer minority in the Mekong Delta, maintaining its distinct rituals and practices that differ markedly from the Mahayana tradition predominant in the rest of Vietnam.

Interestingly, the 20th century saw the emergence of Hoa Hao Buddhism, a reformist movement that simplified Buddhist practice dramatically, eschewing the monastic system and elaborate rituals typical of mainstream Mahayana. Founded by a charismatic healer, it rapidly gained a mass following due to its emphasis on moral living and social welfare. Despite its militant history during the French and American wars, Hoa Hao continues to exert considerable influence in the Mekong region, carefully monitored by the government due to its historical anti-communist stance.

Pagodas and Iconography

Vietnamese Mahayana pagodas often feature statues of Quan Am (Guan Yin), the Bodhisattva of Compassion, who is revered as a protector of women and children and believed to grant sons to devout followers. This figure, often depicted in both male and female forms due to her origins as the male Avalokiteshvara, illustrates the syncretic adaptation of Buddhist iconography in Vietnam, blending native animistic practices with Buddhist theology.

The narrative of Quan Am transforming at the Perfume Pagoda highlights a unique blend of Vietnamese folklore and Mahayana Buddhist theology, making the pagoda a significant spiritual and tourist site. Such stories enrich the cultural tapestry of Vietnam and demonstrate the dynamic way in which Buddhism intertwines with national identity and historical consciousness.

This evolution and adaptation of Buddhism in Vietnam reflect not just religious but also socio-economic changes, showcasing a faith that is not static but vibrant and responsive to the needs of its adherents.