Description of Caodaism

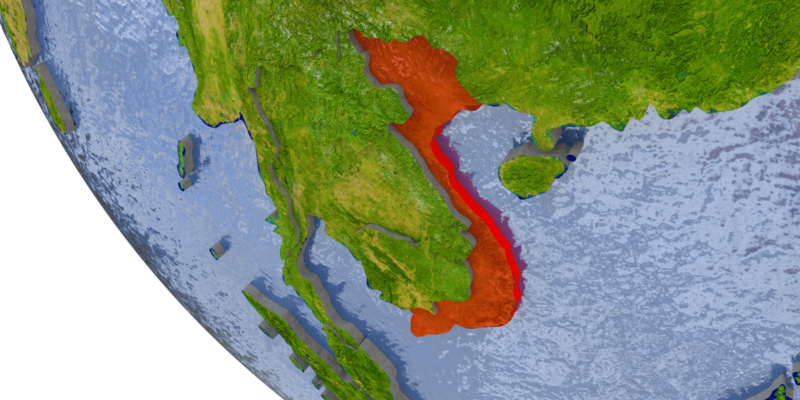

Caodaism, a unique and syncretic religion founded in Vietnam in the early 20th century, represents a fascinating fusion of various religious and philosophical traditions. Established in 1926 by Ngo Van Chieu and a group of his followers, Caodaism (Đạo Cao Đài) seeks to unify the teachings of major world religions into a single, cohesive belief system. This religion blends elements of Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Christianity, and even incorporates aspects of Islam and Hinduism, creating a spiritual framework that emphasizes universal truths and moral principles shared across these diverse traditions. Caodaism is distinguished by its vibrant rituals, colorful temples, and a deep focus on the harmonious coexistence of all faiths. Over the past century, it has garnered a significant following in Vietnam, with millions of adherents, particularly in the southern region, where its holy see is located in Tây Ninh Province. Beyond Vietnam, Caodaism is gradually gaining recognition worldwide as an intriguing example of religious syncretism, attracting interest from scholars and spiritual seekers alike. This religion not only reflects the rich cultural heritage of Vietnam but also embodies a vision of global spiritual unity.

History and Origins

Caodaism was founded in 1926 by Ngô Văn Chiêu, a Vietnamese civil servant who, during his tenure, began to receive divine revelations through spiritual communication. These messages, believed to be from the supreme deity Cao Đài, guided him towards establishing a new religion that would unify the moral teachings of the world’s major faiths. The divine instruction led to the formation of the Cao Đài faith, which emphasizes the belief in a single, supreme god who is the same across all religions. The official founding ceremony of Caodaism took place on November 18, 1926, in Tây Ninh, marking the beginning of a new spiritual movement in Vietnam.

The early development of Caodaism was marked by rapid growth, as the religion attracted a large number of followers from various walks of life, drawn by its inclusive teachings and promises of spiritual unity. This period also saw the construction of the Holy See in Tây Ninh, which remains the central temple and headquarters of the Cao Đài faith. The Holy See, completed in 1955, is a striking architectural marvel, blending traditional Vietnamese, Chinese, and French designs, and serves as a symbol of the religion’s syncretic nature.

Despite its growth, Caodaism faced significant challenges and persecution throughout its history, particularly during periods of political instability in Vietnam. The religion’s emphasis on spiritual and political autonomy led to tensions with both the French colonial authorities and later, the South Vietnamese government. During the Vietnam War, Caodaists were often caught in the crossfire of the conflict, leading to further suppression and difficulties. Despite these challenges, the Cao Đài faith persevered, maintaining its spiritual practices and continuing to attract followers. The resilience of Caodaism, even in the face of persecution, highlights the deep commitment of its adherents and the enduring appeal of its teachings. Today, Caodaism stands as a testament to the enduring spirit of religious syncretism and the quest for universal truth.

Key Beliefs and Practices

At the heart of Caodaism is the belief in the “One Supreme Being,” known as “Đức Cao Đài,” who is regarded as the ultimate creator and ruler of the universe. Caodaists believe that this supreme deity is the same divine force recognized by all religions, transcending individual faiths and uniting them under a common spiritual truth. This central belief emphasizes the universality of God and the importance of harmony among all religious traditions.

Caodaism also places great importance on the existence of spirits and the practice of ancestor veneration. Followers believe that the souls of the deceased continue to influence the living, and honoring ancestors through rituals and offerings is a way to maintain a connection with them and ensure their protection and guidance. Spiritism, or communication with spirits, is a common practice in Caodaism, often conducted during rituals and ceremonies to seek wisdom and guidance from the spiritual realm.

Meditation, prayer, and ritual practices are integral to the spiritual life of Caodaists. These practices are designed to cultivate spiritual growth, purify the soul, and strengthen the connection with the divine. Meditation is particularly emphasized as a means of achieving inner peace and enlightenment, while prayer and rituals help maintain a sense of community and devotion. The daily prayers, which are performed at the Cao Đài temples, involve reciting sacred texts and offering incense to the divine.

Moral conduct is another cornerstone of Caodaism, with a strong emphasis on living a virtuous life. Followers are encouraged to practice charity, compassion, and non-violence in their daily lives, reflecting the religion’s commitment to promoting harmony and kindness in the world. The teachings of Caodaism stress the importance of self-discipline and ethical behavior, with the ultimate goal of achieving spiritual liberation and reuniting with the Supreme Being.

The Caodai calendar, which blends elements of the lunar and solar calendars, plays a significant role in religious observances. The calendar dictates the timing of important festivals and rituals, such as Tết Nguyên Đán (Lunar New Year), which is celebrated with great fervor by Caodaists. Other significant events include the commemoration of Đức Cao Đài’s revelation and the founding of the religion, as well as ceremonies honoring saints, martyrs, and ancestors. These observances not only reinforce the spiritual teachings of Caodaism but also serve to strengthen the bonds within the community.

My own experience attending a Caodai service in Tây Ninh offered a profound glimpse into the religion’s rich tapestry of beliefs and practices. The ritualistic prayers, vibrant costumes, and deeply reverent atmosphere highlighted the deep devotion of the Caodaists and their commitment to a life of spiritual pursuit and moral integrity. The harmonious blending of diverse religious traditions into a unified practice was both awe-inspiring and deeply moving, underscoring Caodaism’s message of universal peace and unity.

Organizational Structure

Caodaism is characterized by a well-defined hierarchical structure, with the Pope serving as the supreme leader of the religion. The Pope, or “Giáo Tông,” is considered the earthly representative of Đức Cao Đài, the Supreme Being, and holds the highest spiritual authority within the Caodai church. The Pope is responsible for overseeing the entire religious organization, guiding the spiritual development of its followers, and maintaining the integrity of the faith’s teachings.

Beneath the Pope are various levels of religious officials, including cardinals, bishops, priests, and other clergy members who play crucial roles in administering the faith. Cardinals (“Chưởng Pháp”) and bishops (“Giám Mục”) are responsible for governing specific dioceses or regions, ensuring that the religious practices and teachings are upheld consistently across the Caodai community. Priests (“Giáo Hữu” and “Giáo Sư”) serve as spiritual leaders within local temples, conducting rituals, leading prayers, and offering guidance to the faithful. Each of these roles is essential in maintaining the spiritual and organizational coherence of Caodaism, with duties ranging from performing sacred ceremonies to managing the day-to-day operations of temples and religious institutions.

The Holy See in Tây Ninh, known as “Tòa Thánh Tây Ninh,” holds a central place in the organizational structure of Caodaism. It serves as the spiritual headquarters of the religion, where the Pope resides and where major religious events and ceremonies are held. The Holy See is an expansive complex, featuring the Great Divine Temple (“Đền Thánh”)—an architectural marvel that symbolizes the syncretic nature of Caodaism, with its design elements reflecting Buddhist, Taoist, and Christian influences. The Holy See is not only the administrative heart of the religion but also a pilgrimage site for Caodaists, attracting thousands of visitors during important festivals and religious observances.

Beyond the Holy See, Caodaism has established a network of temples and communities spread across Vietnam and in various parts of the world. These temples, known as “Thánh Thất,” serve as local centers of worship, where followers gather for prayer, meditation, and community events. The global spread of Caodaism, particularly in countries with large Vietnamese diaspora communities such as the United States, Australia, and France, highlights the religion’s growing influence and the dedication of its followers to preserving their spiritual traditions.

My visit to the Holy See in Tây Ninh was a deeply impactful experience. Walking through the vast temple complex, I could sense the profound spiritual energy that permeates the place. The intricate architecture, the solemn ceremonies led by high-ranking clergy, and the palpable devotion of the worshippers all underscored the importance of the Holy See as the heart of Caodaism. The experience deepened my understanding of how the religion’s organizational structure supports both the spiritual and communal aspects of the faith, ensuring that its teachings and practices continue to thrive both in Vietnam and around the world.

Symbolism and Iconography

Symbolism and iconography play a central role in Caodaism, with various symbols and figures imbued with deep spiritual significance. The most prominent symbol in Caodaism is the Divine Eye, known as the “Thiên Nhãn,” which represents the all-seeing eye of God, or Đức Cao Đài. This symbol, often depicted as a left eye enclosed in a triangle, is a powerful reminder of God’s omnipresence, watching over the universe and guiding the faithful on their spiritual journey. The Divine Eye is prominently featured in Caodai temples, typically placed at the highest point within the sanctuary, serving as the focal point during worship and rituals.

In addition to the Divine Eye, other important symbols in Caodaism include the yin-yang symbol, which represents the balance of opposites and the harmony of the universe. The dragon and phoenix are also frequently depicted in Caodai iconography, symbolizing power, prosperity, and the dynamic interplay of male and female energies. These mythical creatures are often seen adorning temple gates, altars, and ceremonial items, reflecting their importance in Caodai cosmology. Furthermore, various religious figures, including the Buddha, Lao Tzu, Confucius, and Jesus Christ, are revered in Caodaism, symbolizing the syncretic nature of the faith and its respect for multiple religious traditions.

The vibrant colors and intricate designs found in Caodai temples and artwork are another hallmark of the religion’s rich symbolic tradition. Temples are adorned with vivid hues—yellow, red, blue, and white—each representing different aspects of the divine and spiritual principles. Yellow symbolizes Buddhism, blue represents Taoism, and red signifies Confucianism, while white stands for purity and clarity. These colors are not only visually striking but also serve as a reminder of the harmonious coexistence of various spiritual paths within Caodaism.

The significance of these symbols extends into Caodai rituals and practices, where they are used to enhance spiritual awareness and deepen the connection with the divine. For example, during prayer and meditation, the presence of the Divine Eye reminds worshippers of God’s constant presence, encouraging mindfulness and devotion. The use of yin-yang symbols and other iconography in temple ceremonies emphasizes the importance of balance and harmony in both the physical and spiritual realms.

During my visit to the Holy See in Tây Ninh, I was struck by the sheer beauty and complexity of the temple’s symbolism. The Divine Eye, with its penetrating gaze, seemed to watch over the entire sanctuary, creating an atmosphere of reverence and spiritual focus. The intricate carvings of dragons and phoenixes, combined with the temple’s vibrant color scheme, conveyed a sense of power, harmony, and unity that resonated deeply with me. Observing the rituals, I could see how these symbols were woven into every aspect of Caodai practice, from the architecture to the ceremonies, reinforcing the faith’s core beliefs and guiding its followers on their spiritual journey.

Caodaism’s Impact on Vietnamese Society

Caodaism has played a significant role in shaping Vietnamese culture and identity, particularly in the southern regions of the country where the religion originated and flourished. As a uniquely Vietnamese faith that blends elements of various world religions, Caodaism reflects the country’s long history of cultural synthesis and adaptability. The religion’s emphasis on moral conduct, spiritual unity, and respect for diverse beliefs has contributed to the development of a cultural identity that values harmony, community, and tolerance. This syncretic approach has resonated deeply with many Vietnamese, helping to forge a sense of national identity that embraces both tradition and inclusivity.

Throughout Vietnamese history, Caodaism has also had a notable influence on social and political movements. During the French colonial period, Caodaism emerged as a significant force advocating for Vietnamese autonomy and independence. The religion’s leaders and followers were active in various nationalist movements, seeking to preserve Vietnamese culture and values in the face of foreign domination. During the mid-20th century, Caodaism continued to play a role in the country’s social and political landscape, with its adherents involved in both resistance efforts against colonial powers and in the complex political dynamics of post-colonial Vietnam.

Beyond its political influence, Caodaism has made substantial contributions to education, healthcare, and charitable activities in Vietnam. The religion’s teachings emphasize the importance of charity and social welfare, leading to the establishment of numerous schools, hospitals, and orphanages, particularly in the areas surrounding Tây Ninh. These institutions have provided vital services to the local population, often filling gaps in government-provided services. For example, Caodai schools have educated generations of Vietnamese children, while Caodai-run healthcare facilities have offered medical care to those in need, regardless of their religious affiliation. The religion’s commitment to social welfare has helped improve the lives of many and has strengthened the bonds within communities.

In the modern world, there are ongoing efforts to preserve and promote Caodai traditions, both within Vietnam and among the global Vietnamese diaspora. These efforts include the restoration of temples, the documentation of religious texts, and the organization of cultural events that celebrate Caodaism’s rich heritage. Despite the challenges posed by modernization and globalization, Caodaists remain dedicated to maintaining their religious practices and passing them on to future generations. This dedication is evident in the vibrant celebrations of Caodai festivals, the continued operation of Caodai institutions, and the active engagement of the community in religious and cultural preservation.

During my travels in Vietnam, I witnessed firsthand the profound impact Caodaism has had on local communities, particularly in Tây Ninh. The Holy See, with its bustling activity and constant flow of pilgrims, serves as a testament to the religion’s enduring significance. The charitable works carried out by the Caodai community, from running orphanages to providing free medical clinics, reflect the deep commitment to social responsibility that lies at the heart of the faith. Moreover, the pride that Caodaists take in their cultural and religious identity is palpable, driving their efforts to ensure that their traditions continue to thrive in an increasingly modernized world. The resilience and influence of Caodaism in Vietnamese society are clear indicators of the religion’s lasting legacy and its ongoing relevance in shaping the cultural and spiritual landscape of Vietnam.

Conclusion

Caodaism stands as a remarkable and unique religion, deeply rooted in Vietnamese history and culture. From its founding in the early 20th century by Ngô Văn Chiêu to its growth as a major spiritual force, Caodaism has woven together a rich tapestry of beliefs and practices that draw from both Eastern and Western religious traditions. Its central tenets—belief in the One Supreme Being, the significance of ancestor veneration, and the emphasis on moral conduct and charity—are reflected in its vibrant rituals, symbolic iconography, and the daily lives of its followers. Caodaism’s impact on Vietnamese society is profound, influencing not only the spiritual but also the social and political spheres, while contributing to education, healthcare, and charitable activities across the country.

The religion’s unique synthesis of Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Christianity, and other spiritual traditions makes it a distinctive faith that transcends cultural and religious boundaries. This blend of diverse philosophies is a testament to Caodaism’s core principle of universal spiritual unity, which continues to resonate with millions of adherents in Vietnam and around the world. As a vibrant and influential faith, Caodaism offers a compelling example of how different religious traditions can come together to form a cohesive and harmonious belief system.

For those interested in exploring the complexities of global spirituality, Caodaism presents a fascinating case study. Its rich history, profound teachings, and enduring cultural significance invite further study and appreciation. By delving deeper into the world of Caodaism, one can gain a greater understanding of the ways in which religions can evolve, interact, and influence the broader cultural landscape. In a world often marked by division, Caodaism stands as a beacon of inclusivity and unity, offering valuable lessons in the power of spiritual synthesis and the enduring quest for universal truth.